Internationally known as one of the world’s foremost painters of wildlife, Les Kouba’s deep understanding of the subject stems from his youth on a Minnesota farm. Impressed by the beauty of nature at an early age, he was afforded ample opportunity to observe and study wildlife in their natural habitat.

At 14, Les Kouba supplemented his natural artistic talent with a correspondence school art course. Read moreInternationally known as one of the world’s foremost painters of wildlife, Les Kouba’s deep understanding of the subject stems from his youth on a Minnesota farm. Impressed by the beauty of nature at an early age, he was afforded ample opportunity to observe and study wildlife in their natural habitat.

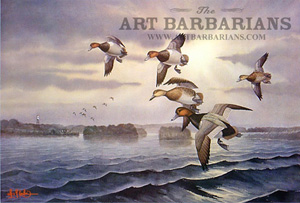

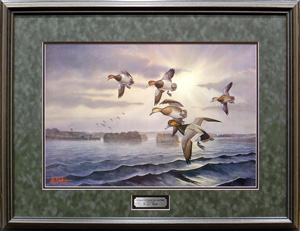

At 14, Les Kouba supplemented his natural artistic talent with a correspondence school art course. The guidance of professional art instruction was invaluable in helping develop his own unusual technique which immediately identifies his work. His exciting oils, and dynamic water colors are known worldwide and reputed to be some of the most authentic portraits of wildlife existence.

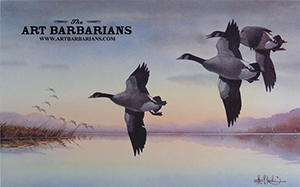

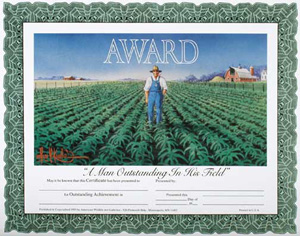

In addition, Kouba’s works have appeared on the covers if many national magazines, as illustrations for outdoor books and he is nationally known as an award winning package designer. He has also gained fame as the designer of Federal Duck Stamps. The artist was honored in “Men of Achievement 1974”, “Who’s Who in Art,” International Directory of Arts and “Who’s Who,” elected 1976-77 D.U. “Artist of the Year,” winner of Minnesota’s First Waterfowl Stamp Competition for the 1978 stamp and, in 1980, being of Czech heritage, recipient of the “King Charles International Award,” for outstading achievements in art.

An extremely active supporter of “Ducks Unlimited,” an international organization of sportsmen who foster the propagation of waterfowl, Les says “Ducks have been good to me. . .I want to be good to them.” Les Kouba’s contributions in artwork to Ducks Unlimited now exceeds his goal set for $1,000,000.

He is the Founder and Director of American Wildlife Art Galleries of Minneapolis, which houses one of the largest collections of original wildlife art in the Nation. The gallery exhibits hundreds of vividly exciting water color and oil paintings by famous American wildlife artists.

Leslie C. Kouba, dean of Minnesota's wildlife artists, is a self-made man who describes himself as 52 percent businessman and 48 percent artist. "I've made my way in this world by following three principles: First, pick the thing you like to do best; then, learn everything you can about it; and finally, be willing to work harder than anyone else in that field. Kouba's secret to success: work. It's that simple."

Les Kouba is a celebrity who loves the public. If you happen by the American Wildlife Galleries in the Plymouth Building on Sixth Street in downtown Minneapolis, there is a good chance you will meet him. He's the guy who wears confidence like a second set of clothes. His gray hair is slicked straight back off the forehead. His trifocal glasses perch on his nose above a mustache waxed to a razor sharp point. His bolo tie is looped around his shirt collar and his customary plaid sports jacket hangs on a rack in the corner. His blue eyes flash and sparkle as he spins yarns and dispenses bits and pieces of homespun wisdom to anyone within earshot. At 71, Kouba enjoys life.

Comfortably sitting in his favorite chair, Kouba leans back and with a twinkle in his eye, he says: "You know, this rooster was hatched during a big snow storm. I arrived on February 3, 1917, during a whale of a blizzard at Hutchinson, a small picturesque town in west central Minnesota. I was born on a farm about two miles east of town. My parents, Anthony and Sophie Kouba, were first generation Americans. Their parents had emigrated to this country from Prague, Czechoslovakia.

"I was the middle child with a brother on each side of me. My parents owned their own small dairy operation. Those were the days," says Kouba, " when you had a handful of chickens, a patch of dirt for a vegetable garden, a few pigs and a dozen milk cows. You tried to scratch out a living any way you could. My Grandpa Philipi, my mother's father, had 120 colonies of bees, and, as you well know," says Kouba with a hearty laugh, "that's a pretty sweet business selling that honey stuff."

The farm not only provided the Kouba family with a means to earn a living, but it also served as a never-ending playground for three active boys. Les, with brothers Harry and Ernie in tow, often roamed the surrounding fields and woods absorbing the lessons of nature as they went along.

Kouba's favorite companion on these outdoor adventures was his dog, Bobby. "He was the best friend I had when I was growing up. He was just a mutt, nothing fancy, but I loved him all the same," says Kouba. "I remember one time when he seemed to have disappeared. I didn't think much of it at first, but after three days I figured he was a goner. I was completely heartbroken. It was Thanksgiving Day and I took a walk out in the plowed field to hunt jackrabbits. As I looked around for rabbits, I spotted something hanging from the top of the fence. It was Bobby. Somehow, when he was out chasing jackrabbits, he got tangled up in the woven wire fence and couldn't free himself. He was in pretty rough shape when I found him. I carried him home and we nursed him back to health. We put Watkins' Carbolic Salve, the ointment in the tin, on his damaged leg-that brown stuff could cure anything. He ended up having three good legs instead of four, but it never seemed to bother him chasing after those jackrabbits. We had a lot to be thankful for that Thanksgiving.

"My father," continues Kouba, "contributed to my early appreciation of nature. He taught me a lot of the little tricks in hunting, trapping, and later, fishing. He instilled in me at an early age, the sheer enjoyment of being outdoors. Back when I was a kid, it was really something to go hunting. Those were the days when the ducks and geese were so plentiful that the sky turned black when the flocks passed by overhead. These experiences were so exciting to me that I started to portray these happenings on bits of paper that I always carried with me. Consequently, I drew my impressions of birds, game animals, big game and fish-everything across the board. Because I actually hunted, I developed an early understanding of all the background skills necessary to be successful at my future career as a wildlife artist."

Les C Kouba decided early in life that farming wasn't for him. "I knew I could draw when I was about 8 years old. I think I made up my mind about then that I wanted to be an artist when I grew up. In fact," says Kouba, "many of the buildings on the farm still show traces of my early enthusiastic attempts at painting. And I was quite convinced I was on the right track when I sold my first painting at age 11 to a prosperous German farmer who lived near Hutchinson.

One of the things I like best about being an artist is when I come up with an idea, I can grab a pencil and paper and just sketch it out," says Kouba. "My mind is always full of possibilities for paintings. I often get a new idea by watching and listening to the remarks my customers make when they visit the gallery. I'm keenly interested in what they see, what they're looking for, and what they admire in a painting.

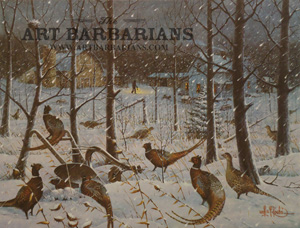

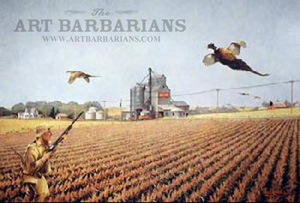

"By listening, I found out that Headin' for Shelter with those 13 pheasants and that little cottontail rabbit turned the dudes on so much-they had to have another and another. I released the print in 1974 at $40. Almost instantly it clicked, sending the value soaring to over $2,000 if you were lucky enough to find one.

"I never really anticipated that Headin' for Shelter, In Shelter, and finally, Leavin' Shelter would be the large sellers they turned out to be. I knew I had a good thing going -- I was painting something that hadn't been painted before. This made it very exciting for me. I had seen your typical run-of-the-mill pheasant art before. I was doing something completely different. I was pouring true detail and nostalgia into the painting. I painted it at the right time in the right way. Most artists would shy away from those images because they're so detailed and involved. In terms of art study, they may be too 'busy.' But I go beyond any classic rules. I paint a scene how I think it should be. That's my guiding rule.

"One of the problems with painters today," says Kouba, "is they haven't experienced things firsthand. I grew up on a farm. I didn't have to go to the library to learn how to paint a barn. I helped build them, clean them, work in them. I know what a barn is, and I also know what farm machinery is and what it's used for. A lot of these kinds of mistakes are made because the artist doesn't know the subject matter. I only paint what I know. That's my secret.

"I also believe," says Kouba, "that an artist has to experiment in order to learn. I can paint in any medium. I've mastered both watercolors and oils. I've learned stone lithography, dry point etching and aquatint. In more recent years, I've also studied the process of photo-lithography and I now have a good grasp of that as well.

"I was never satisfied," he continues, "knowing just a little bit about something. I always wanted to know the whole ball of wax. I've found life to be an ongoing learning process.

"When I sold that first little painting many years ago, I thought, 'Wow! This is the way to go.' I would have been a painter no matter what price my paintings earned.

"I believe to be successful you must work at something you enjoy. For me, the thing I liked to do best was paint wildlife," says Kouba. "I wasn't content to look out the window for my ideas. I wanted to experience and learn all about the outdoors. I loved it so much, I'd be painting even if I didn't make any money at it. Being well paid for my efforts is a bonus.

"I always made a point of turning every experience into a learning opportunity," says Kouba. "Early in my career, I did a short stint as a taxidermist. I made careful anatomical studies of my mounts so that I would develop a true understanding of how everything fit together and worked.

"I also kept a drawing pad within easy reach. That way, anything that caught my eye, I could quickly sketch it. I not only studied the birds, animals, and fish that went into my paintings, but the actual settings that make my work authentic as well.

"With the invention of high quality, color film, I added the camera to my bag of tricks. There's nothing like it for catching detail. I've taken tens of thousands of Kodachromes of just about everything that would be of possible use in a painting.

"I don't just photograph a pretty landscape type scene. I get into the nitty gritty-where I go to the trouble of filming individual corn stalks, reeds, rocks, wild rice, pine trees, shorelines, tree stumps just about anything. You never know when you just might need a certain type of grass or sky formation to give a painting that special touch.

"'I've also taken miles of slow motion movie picture film of birds and animals-action footage. I go after ducks and geese to get that wing motion of the birds as they rise, fly, or drop into a marsh.

"Keep in mind, however, that the camera is only a tool. The painting comes from your heart and is fueled by your imagination.

"It's my tremendous attention to authentic detail that marks the difference between the artist who knows what he is painting and the one who thinks he can dream about something and make it look real on canvas.

"'I've found there's just too many collectors who go hunting and fishing and know what the outdoors looks like. They also know what ducks, geese, deer and fish look like. They won't be fooled and they want their wildlife paintings to look like the real thing. From his book, The Legacy of Les C. Kouba.

“Of all the paintings I’ve done, “Cry of the Loon” is the one my wife, Oriall, kept. The scene is typical of many of the trips we’ve taken through the years…When dusk comes in this quiet, very serene Northland, that’s when you’ll hear the almost eerie cry of the loon.”

"That first painting was of a deer at the water's edge with some pine trees in the background," remembers Kouba. "It was something that I had created completely myself. I had hardly any materials-just junk-whatever I was able to pick up on the farm. I used a two-foot wide piece of upson board for my canvas. At that time, upson board was used for attic insulation. I did it in oil paints, and 'oil' in those days meant anything that wasn't watercolor. I used just about any kind of pigment I could lay my hands on-house paint, implement paint, and enamels-you name it.

"I sold that painting for eight dollars, a king's ransom in those days," says Kouba. "It doesn't seem like much by today's standards, but keep in mind that was in 1928, 'when a dime was as big as a wagon wheel.' To put it into perspective, my father's total income from his dairy business was $22 for the month."

That early sale went a long way in convincing Kouba's parents that his artistic skills were worth developing. Art talent, however, was nothing new to Kouba's father, Tony. He had the gift to draw and his father-in-law, Grandpa Philipi, was quite a penman "beautiful Spencerian script and calligraphy. He was also a master cabinet maker and carpenter," remembers Kouba.

"My brother Ernie was a real good artist, too. I asked him once why he hadn't stayed with it. He said: 'I'll tell you why. I'd do a painting and then I'd look at yours and I figured, forget it. I'd never catch up with that dude."'

Delores Saar, a childhood friend of Kouba's, remembers visiting one day and being greeted with a bed sheet stretched across the wall. "Les and his brother Harry were always into one thing or another," says Saar. "It seems on this occasion, the Kouba brothers had invented a type of movie projector. Les drew pictures of an airplane in different positions on a piece of glass. The strip of glass was inserted into the 'projector,' a device made from a flashlight and a handful of other odds-and-ends. By moving the glass strip, the image of the airplane was projected onto the 'screen' giving the illusion that the airplane was moving across the wall. It was really something."

Kouba's parents supported Les's interest in art by enrolling him at age 14 in a correspondence course sponsored by the Federal Schools in Minneapolis.

"The name has been changed since I went there," says Kouba. "It's now known as Art Instruction, the 'Draw-Me' school. It offers all the basics but it doesn't overly influence technique. You don't end up painting like your instructor. I really learned a lot from that school. I will always be thankful that I had the opportunity to take the course.

"Many artists I've found today," says Kouba, "could benefit from some of those early lessons."

"Frankly," he adds, "this correspondence course was a wonderful opportunity for me. I could fit it in with my farm chores and after school sports. I could have my training and not be nailed down to a certain schedule. Right to this day, at age 71, I like that kind of flexibility."

Les Kouba, who called everybody "dude", checked out (as he would have put it) on September 13, at the age of 81. Mr. Kouba, who designed 1958 and 1967 Federal Duck Stamps, along with stamps for Minnesota and North Dakota, was living at the Mt. Olivet Nursing home at the time of his death. An unfinished painting remained in his room, as he continued to paint until the end.

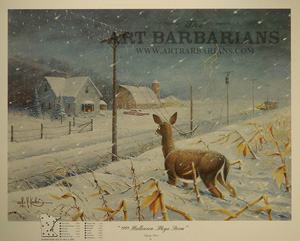

It was a strange coincidence that Mr. Kouba passed away on the 13th, as his trademark was the number 13. Many of his paintings featured "13" of a particular item. It was a habit formed more than 40 years ago, when a friend noticed his painting often contained 13 similar objects. His famed lutefisk stamp print features a thermometer that reads 13 degrees.

He discovered his talent when he was 11; he sold his first painting to a wealthy German farmer for $12. It was an enormous sum in the late 1920’s. At 14, he enrolled in a correspondence art course and later attended a private art academy after being kicked out of public school.

His early years were spent traveling the United States, painting Coca-Cola signs before the advent of decals. His sharp eye did not like the Coke logo; he decided it needed more flair, so he sloped and fattened the letters.

Coke officials got wind of Kouba’s redesign, tracked him down and were impressed. Kouba received a handsome check in return. Mr. Kouba opened a commercial art studio in Minneapolis called Kouba Advertising Art. Some of his famous contributions to the commercial art scene included: The Old Dutch windmill on potato chip bags, Schmidt beer wildlife scenes, and the Red Owl logo for the grocery store chain.

Kouba was one of the first artists to create wildlife paintings in a series. His "Shelter" series, three works depicting 13 pheasants searching for, finding, and leaving a farmer’s shelterbelt during a storm, set the standard for the genre.

His wildlife paintings range from dark and brooding storms to brilliant sunsets to a warm moonlit night. Admirers often say the paintings remind them of places they have been.

less

Internationally known as one of the world’s foremost painters of wildlife, Les Kouba’s deep understanding of the subject stems from his youth on a Minnesota farm. Impressed by the beauty of nature at an early age, he was afforded ample opportunity to observe and study wildlife in their natural habitat.

At 14, Les Kouba supplemented his natural artistic talent with a correspondence school art course. Read moreInternationally known as one of the world’s foremost painters of wildlife, Les Kouba’s deep understanding of the subject stems from his youth on a Minnesota farm. Impressed by the beauty of nature at an early age, he was afforded ample opportunity to observe and study wildlife in their natural habitat.

At 14, Les Kouba supplemented his natural artistic talent with a correspondence school art course. The guidance of professional art instruction was invaluable in helping develop his own unusual technique which immediately identifies his work. His exciting oils, and dynamic water colors are known worldwide and reputed to be some of the most authentic portraits of wildlife existence.

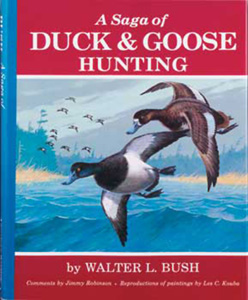

In addition, Kouba’s works have appeared on the covers if many national magazines, as illustrations for outdoor books and he is nationally known as an award winning package designer. He has also gained fame as the designer of Federal Duck Stamps. The artist was honored in “Men of Achievement 1974”, “Who’s Who in Art,” International Directory of Arts and “Who’s Who,” elected 1976-77 D.U. “Artist of the Year,” winner of Minnesota’s First Waterfowl Stamp Competition for the 1978 stamp and, in 1980, being of Czech heritage, recipient of the “King Charles International Award,” for outstading achievements in art.

An extremely active supporter of “Ducks Unlimited,” an international organization of sportsmen who foster the propagation of waterfowl, Les says “Ducks have been good to me. . .I want to be good to them.” Les Kouba’s contributions in artwork to Ducks Unlimited now exceeds his goal set for $1,000,000.

He is the Founder and Director of American Wildlife Art Galleries of Minneapolis, which houses one of the largest collections of original wildlife art in the Nation. The gallery exhibits hundreds of vividly exciting water color and oil paintings by famous American wildlife artists.

Leslie C. Kouba, dean of Minnesota's wildlife artists, is a self-made man who describes himself as 52 percent businessman and 48 percent artist. "I've made my way in this world by following three principles: First, pick the thing you like to do best; then, learn everything you can about it; and finally, be willing to work harder than anyone else in that field. Kouba's secret to success: work. It's that simple."

Les Kouba is a celebrity who loves the public. If you happen by the American Wildlife Galleries in the Plymouth Building on Sixth Street in downtown Minneapolis, there is a good chance you will meet him. He's the guy who wears confidence like a second set of clothes. His gray hair is slicked straight back off the forehead. His trifocal glasses perch on his nose above a mustache waxed to a razor sharp point. His bolo tie is looped around his shirt collar and his customary plaid sports jacket hangs on a rack in the corner. His blue eyes flash and sparkle as he spins yarns and dispenses bits and pieces of homespun wisdom to anyone within earshot. At 71, Kouba enjoys life.

Comfortably sitting in his favorite chair, Kouba leans back and with a twinkle in his eye, he says: "You know, this rooster was hatched during a big snow storm. I arrived on February 3, 1917, during a whale of a blizzard at Hutchinson, a small picturesque town in west central Minnesota. I was born on a farm about two miles east of town. My parents, Anthony and Sophie Kouba, were first generation Americans. Their parents had emigrated to this country from Prague, Czechoslovakia.

"I was the middle child with a brother on each side of me. My parents owned their own small dairy operation. Those were the days," says Kouba, " when you had a handful of chickens, a patch of dirt for a vegetable garden, a few pigs and a dozen milk cows. You tried to scratch out a living any way you could. My Grandpa Philipi, my mother's father, had 120 colonies of bees, and, as you well know," says Kouba with a hearty laugh, "that's a pretty sweet business selling that honey stuff."

The farm not only provided the Kouba family with a means to earn a living, but it also served as a never-ending playground for three active boys. Les, with brothers Harry and Ernie in tow, often roamed the surrounding fields and woods absorbing the lessons of nature as they went along.

Kouba's favorite companion on these outdoor adventures was his dog, Bobby. "He was the best friend I had when I was growing up. He was just a mutt, nothing fancy, but I loved him all the same," says Kouba. "I remember one time when he seemed to have disappeared. I didn't think much of it at first, but after three days I figured he was a goner. I was completely heartbroken. It was Thanksgiving Day and I took a walk out in the plowed field to hunt jackrabbits. As I looked around for rabbits, I spotted something hanging from the top of the fence. It was Bobby. Somehow, when he was out chasing jackrabbits, he got tangled up in the woven wire fence and couldn't free himself. He was in pretty rough shape when I found him. I carried him home and we nursed him back to health. We put Watkins' Carbolic Salve, the ointment in the tin, on his damaged leg-that brown stuff could cure anything. He ended up having three good legs instead of four, but it never seemed to bother him chasing after those jackrabbits. We had a lot to be thankful for that Thanksgiving.

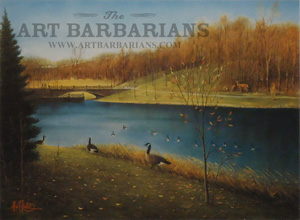

"My father," continues Kouba, "contributed to my early appreciation of nature. He taught me a lot of the little tricks in hunting, trapping, and later, fishing. He instilled in me at an early age, the sheer enjoyment of being outdoors. Back when I was a kid, it was really something to go hunting. Those were the days when the ducks and geese were so plentiful that the sky turned black when the flocks passed by overhead. These experiences were so exciting to me that I started to portray these happenings on bits of paper that I always carried with me. Consequently, I drew my impressions of birds, game animals, big game and fish-everything across the board. Because I actually hunted, I developed an early understanding of all the background skills necessary to be successful at my future career as a wildlife artist."

Les C Kouba decided early in life that farming wasn't for him. "I knew I could draw when I was about 8 years old. I think I made up my mind about then that I wanted to be an artist when I grew up. In fact," says Kouba, "many of the buildings on the farm still show traces of my early enthusiastic attempts at painting. And I was quite convinced I was on the right track when I sold my first painting at age 11 to a prosperous German farmer who lived near Hutchinson.

One of the things I like best about being an artist is when I come up with an idea, I can grab a pencil and paper and just sketch it out," says Kouba. "My mind is always full of possibilities for paintings. I often get a new idea by watching and listening to the remarks my customers make when they visit the gallery. I'm keenly interested in what they see, what they're looking for, and what they admire in a painting.

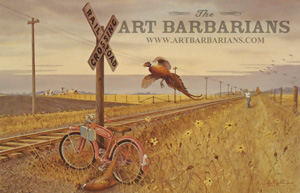

"By listening, I found out that Headin' for Shelter with those 13 pheasants and that little cottontail rabbit turned the dudes on so much-they had to have another and another. I released the print in 1974 at $40. Almost instantly it clicked, sending the value soaring to over $2,000 if you were lucky enough to find one.

"I never really anticipated that Headin' for Shelter, In Shelter, and finally, Leavin' Shelter would be the large sellers they turned out to be. I knew I had a good thing going -- I was painting something that hadn't been painted before. This made it very exciting for me. I had seen your typical run-of-the-mill pheasant art before. I was doing something completely different. I was pouring true detail and nostalgia into the painting. I painted it at the right time in the right way. Most artists would shy away from those images because they're so detailed and involved. In terms of art study, they may be too 'busy.' But I go beyond any classic rules. I paint a scene how I think it should be. That's my guiding rule.

"One of the problems with painters today," says Kouba, "is they haven't experienced things firsthand. I grew up on a farm. I didn't have to go to the library to learn how to paint a barn. I helped build them, clean them, work in them. I know what a barn is, and I also know what farm machinery is and what it's used for. A lot of these kinds of mistakes are made because the artist doesn't know the subject matter. I only paint what I know. That's my secret.

"I also believe," says Kouba, "that an artist has to experiment in order to learn. I can paint in any medium. I've mastered both watercolors and oils. I've learned stone lithography, dry point etching and aquatint. In more recent years, I've also studied the process of photo-lithography and I now have a good grasp of that as well.

"I was never satisfied," he continues, "knowing just a little bit about something. I always wanted to know the whole ball of wax. I've found life to be an ongoing learning process.

"When I sold that first little painting many years ago, I thought, 'Wow! This is the way to go.' I would have been a painter no matter what price my paintings earned.

"I believe to be successful you must work at something you enjoy. For me, the thing I liked to do best was paint wildlife," says Kouba. "I wasn't content to look out the window for my ideas. I wanted to experience and learn all about the outdoors. I loved it so much, I'd be painting even if I didn't make any money at it. Being well paid for my efforts is a bonus.

"I always made a point of turning every experience into a learning opportunity," says Kouba. "Early in my career, I did a short stint as a taxidermist. I made careful anatomical studies of my mounts so that I would develop a true understanding of how everything fit together and worked.

"I also kept a drawing pad within easy reach. That way, anything that caught my eye, I could quickly sketch it. I not only studied the birds, animals, and fish that went into my paintings, but the actual settings that make my work authentic as well.

"With the invention of high quality, color film, I added the camera to my bag of tricks. There's nothing like it for catching detail. I've taken tens of thousands of Kodachromes of just about everything that would be of possible use in a painting.

"I don't just photograph a pretty landscape type scene. I get into the nitty gritty-where I go to the trouble of filming individual corn stalks, reeds, rocks, wild rice, pine trees, shorelines, tree stumps just about anything. You never know when you just might need a certain type of grass or sky formation to give a painting that special touch.

"'I've also taken miles of slow motion movie picture film of birds and animals-action footage. I go after ducks and geese to get that wing motion of the birds as they rise, fly, or drop into a marsh.

"Keep in mind, however, that the camera is only a tool. The painting comes from your heart and is fueled by your imagination.

"It's my tremendous attention to authentic detail that marks the difference between the artist who knows what he is painting and the one who thinks he can dream about something and make it look real on canvas.

"'I've found there's just too many collectors who go hunting and fishing and know what the outdoors looks like. They also know what ducks, geese, deer and fish look like. They won't be fooled and they want their wildlife paintings to look like the real thing. From his book, The Legacy of Les C. Kouba.

“Of all the paintings I’ve done, “Cry of the Loon” is the one my wife, Oriall, kept. The scene is typical of many of the trips we’ve taken through the years…When dusk comes in this quiet, very serene Northland, that’s when you’ll hear the almost eerie cry of the loon.”

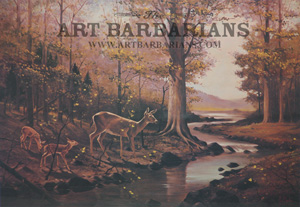

"That first painting was of a deer at the water's edge with some pine trees in the background," remembers Kouba. "It was something that I had created completely myself. I had hardly any materials-just junk-whatever I was able to pick up on the farm. I used a two-foot wide piece of upson board for my canvas. At that time, upson board was used for attic insulation. I did it in oil paints, and 'oil' in those days meant anything that wasn't watercolor. I used just about any kind of pigment I could lay my hands on-house paint, implement paint, and enamels-you name it.

"I sold that painting for eight dollars, a king's ransom in those days," says Kouba. "It doesn't seem like much by today's standards, but keep in mind that was in 1928, 'when a dime was as big as a wagon wheel.' To put it into perspective, my father's total income from his dairy business was $22 for the month."

That early sale went a long way in convincing Kouba's parents that his artistic skills were worth developing. Art talent, however, was nothing new to Kouba's father, Tony. He had the gift to draw and his father-in-law, Grandpa Philipi, was quite a penman "beautiful Spencerian script and calligraphy. He was also a master cabinet maker and carpenter," remembers Kouba.

"My brother Ernie was a real good artist, too. I asked him once why he hadn't stayed with it. He said: 'I'll tell you why. I'd do a painting and then I'd look at yours and I figured, forget it. I'd never catch up with that dude."'

Delores Saar, a childhood friend of Kouba's, remembers visiting one day and being greeted with a bed sheet stretched across the wall. "Les and his brother Harry were always into one thing or another," says Saar. "It seems on this occasion, the Kouba brothers had invented a type of movie projector. Les drew pictures of an airplane in different positions on a piece of glass. The strip of glass was inserted into the 'projector,' a device made from a flashlight and a handful of other odds-and-ends. By moving the glass strip, the image of the airplane was projected onto the 'screen' giving the illusion that the airplane was moving across the wall. It was really something."

Kouba's parents supported Les's interest in art by enrolling him at age 14 in a correspondence course sponsored by the Federal Schools in Minneapolis.

"The name has been changed since I went there," says Kouba. "It's now known as Art Instruction, the 'Draw-Me' school. It offers all the basics but it doesn't overly influence technique. You don't end up painting like your instructor. I really learned a lot from that school. I will always be thankful that I had the opportunity to take the course.

"Many artists I've found today," says Kouba, "could benefit from some of those early lessons."

"Frankly," he adds, "this correspondence course was a wonderful opportunity for me. I could fit it in with my farm chores and after school sports. I could have my training and not be nailed down to a certain schedule. Right to this day, at age 71, I like that kind of flexibility."

Les Kouba, who called everybody "dude", checked out (as he would have put it) on September 13, at the age of 81. Mr. Kouba, who designed 1958 and 1967 Federal Duck Stamps, along with stamps for Minnesota and North Dakota, was living at the Mt. Olivet Nursing home at the time of his death. An unfinished painting remained in his room, as he continued to paint until the end.

It was a strange coincidence that Mr. Kouba passed away on the 13th, as his trademark was the number 13. Many of his paintings featured "13" of a particular item. It was a habit formed more than 40 years ago, when a friend noticed his painting often contained 13 similar objects. His famed lutefisk stamp print features a thermometer that reads 13 degrees.

He discovered his talent when he was 11; he sold his first painting to a wealthy German farmer for $12. It was an enormous sum in the late 1920’s. At 14, he enrolled in a correspondence art course and later attended a private art academy after being kicked out of public school.

His early years were spent traveling the United States, painting Coca-Cola signs before the advent of decals. His sharp eye did not like the Coke logo; he decided it needed more flair, so he sloped and fattened the letters.

Coke officials got wind of Kouba’s redesign, tracked him down and were impressed. Kouba received a handsome check in return. Mr. Kouba opened a commercial art studio in Minneapolis called Kouba Advertising Art. Some of his famous contributions to the commercial art scene included: The Old Dutch windmill on potato chip bags, Schmidt beer wildlife scenes, and the Red Owl logo for the grocery store chain.

Kouba was one of the first artists to create wildlife paintings in a series. His "Shelter" series, three works depicting 13 pheasants searching for, finding, and leaving a farmer’s shelterbelt during a storm, set the standard for the genre.

His wildlife paintings range from dark and brooding storms to brilliant sunsets to a warm moonlit night. Admirers often say the paintings remind them of places they have been.

less

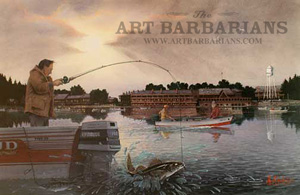

Jumping Brown Trout - Original Painting By Les C. Kouba

|

Jumping Largemouth Bass - Original Painting By Les C. Kouba

|